Tess Bartley loves Verdi’s Requiem. A soprano and also our Choir Manager, she fell in love with the mass at school and shares her stand-out moments from the choral masterpiece.

1992 was an epic year. The Maastricht Treaty was signed, creating the European Union and single currency. Bush and Yeltsin proclaimed the formal end of the Cold War. Bosnia and Herzegovina’s independence was recognised by the UN. South Africa voted to end apartheid. Bill Clinton unseated the incumbent to be elected US President. And, the late Freddie Mercury’s duet with Montserrat Caballe, “Barcelona”, was featured as the official song of the Summer Olympics – the first and, some would say, only successful collaboration between the opera and popular music worlds.

At 13 years old, I wasn’t eminently aware of the historic moments going on around me. I was mostly concerned with how to blindly pitch the first note of Whitney Houston’s “I Will Always Love You” without a tuning fork! But 1992 was a historic year for me too.

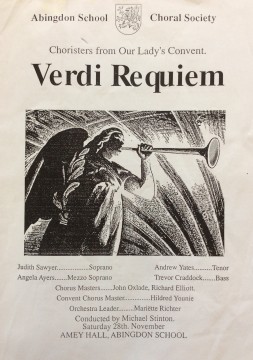

As I entered my third year at secondary school, I began preparations for my first ever concert singing with full orchestra – a performance of Verdi’s iconic Requiem. Having grown up in a traditional church choir, I’d only ever sung chamber music with piano or organ so performing with an orchestra was a whole new world to me. The concert was organised by the Abingdon School Choral Society which was a made up of parents and teachers of the boys studying at Abingdon School. The boys at the school were involved too and my school, Our Lady’s Convent, was asked to contribute some more female voices.

A Smorgasbord of Amazing Moments

From the first utterance of “Requiem” to the final whisper of “Libera me”, I was utterly spellbound by this incredible piece. The entire work is a smorgasbord of amazing moments, like a classical Greatest Hits album all in one piece. I remember the first time I heard the tenor soloist enter with “Kyrie Eleison” and thinking, “Wow, he really wants mercy!” The movement then revs up into a canon of Kyries from soloists and chorus until all performers come together to finish on a blissful and barely audible “Christe eleison”.

Like Mozart before him, Verdi launches straight into the fury and calamity of the Dies Irae. His illustration of impending doom has permeated outside the classical music world where it has featured in movies such as Mad Max: Fury Road and Django Unchained as well as being a regular feature in episodes of the X Factor. This movement also includes my favourite 49 bars of music EVER – the trumpet voluntary. It doesn’t matter how many times I hear it, as the brass builds towards the bass chorus entry of “Tuba mirum spargens sonum” (“The trumpet casting a wondrous sound”), I get shivers down my spine and half expect the heavens to open.

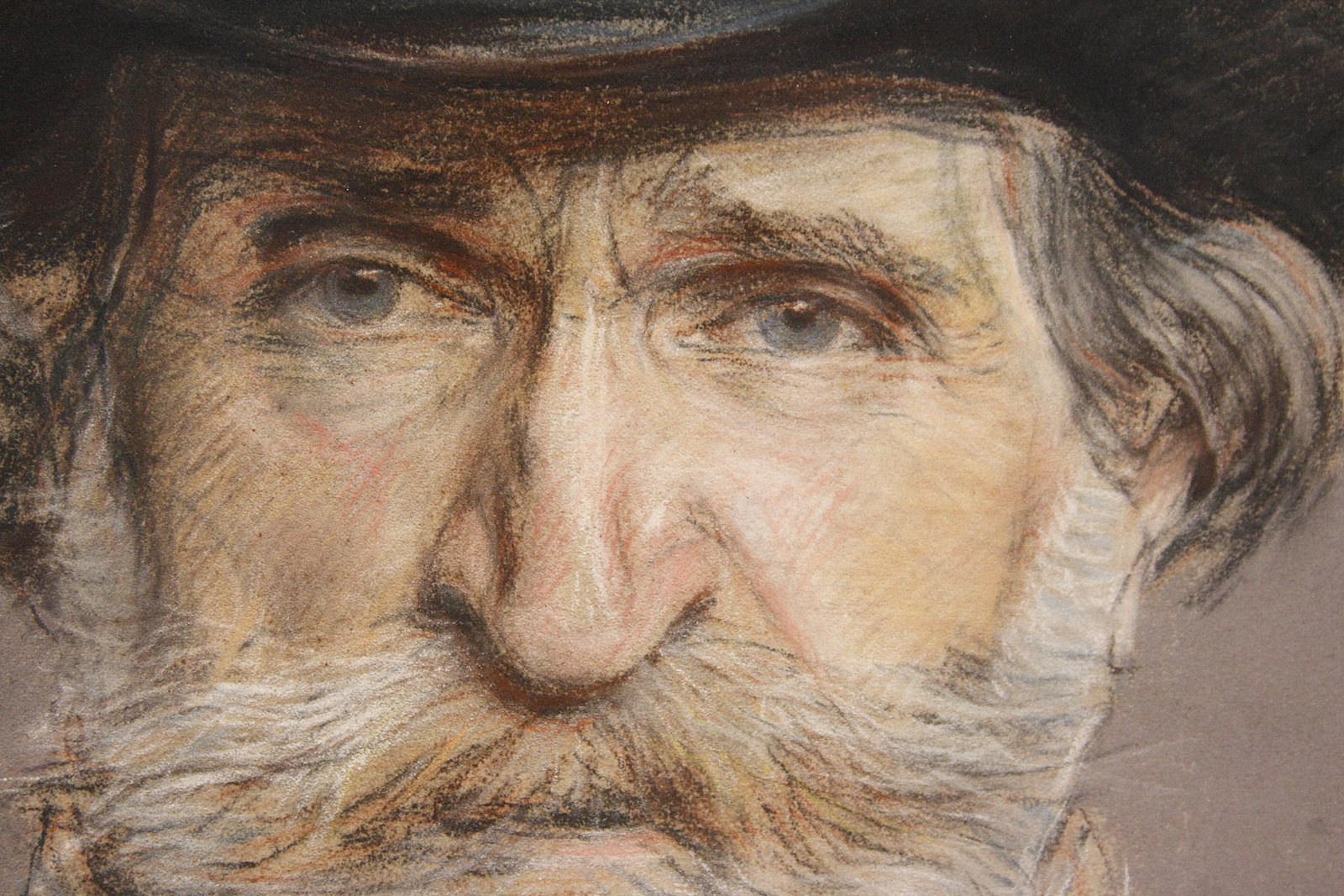

Later, the mezzo soprano darkly proclaims that “nothing will be forgotten or unpunished” before joining with with the bass soloist in the Lacrimosa, a passage of music that, for me, always conjures up a vision of Giuseppe Verdi (aka Joe Green) cycling around a small town in Italy, with tomatoes in the basket of his bike! Imagine something along the lines of a Dolmio advertisement and you’ll be close to my vision, which doesn’t really fit with the words of doom and pity but perhaps it was Verdi’s way of showing that we’re all just mere mortals.

The choir gets a break during the Offertory while the four soloists display their operatic skills and, like many places in this Requiem, we’re reminded that this work was destined for the concert hall and not the church. Then comes the choir’s pièce de résistance – the Sanctus.

Despite the fabulous array of chorus parts in the majority of requiem masses, for the most part the text doesn’t fit well for a happy occasion. But the Sanctus is the exception. Boasting a double choir, this self-contained choral movement provides light relief from the darkness of rest of the piece and, if you’ve got a strong choir, is an excellent option during the signing of the register at a church wedding!

For Concert Hall or Church?

Another indication to me that this piece was for the concert hall not the church is the Agnus Dei. The soprano and mezzo soloists seem to me like mothers, praying together and asking for mercy. Perhaps that’s not what Verdi had intended to visualise but, if it was, in the world of male only church choirs, this analogy wouldn’t have worked at all with a countertenor and boy soprano!

In the next movement, the Lux Aeterna, the soloists remind us again that death is coming. But where is the soprano soloist? Well, she’s preparing for the final movement and her heroic pianissississimo (pppp) top B flat. As she soars up to that note, every soprano in the room is willing her up there, hoping that if we all raise our eyebrows and cheekbones we can help her on her way.

Then it’s our turn. In the fugue, the first sopranos get the opportunity of a lifetime to sing a top C at a decent volume and with the most incredible lead up. As a second soprano, I admit that it’s a note I do miss but I also thoroughly enjoy belting out the lower harmony while the firsts float above me.

Performing Verdi with Maestros

Verdi’s Requiem is, hands down, my favourite piece of choral music to sing and during my 14 years in the London Philharmonic Choir I’ve been lucky enough to perform it several times, including once at the BBC Proms under Semyon Bychkov plus twice at the Royal Festival Hall with Vladimir Jurowski.

If you’ve read any of our choir profiles you’ll have seen several of our members mention how amazing it is to work with the Maestro Jurowski. I was beside myself with excitement in 2008 leading to the first rehearsal with Jurowski and he didn’t disappoint.

His instructions to sing Te decet hymnus “like Palestrina” and return to the soft utterance of Requiem as if “staring into grave of loved one” were swiftly followed by illustrative directions that parts of the Dies irae should feel like “hot lava” and as we build up to the re-entry of the legendary descending chromatic scales. In the passage with quieter choral interjections, Jurowski asked that we imagine a storm is coming, getting closer and closer and then, when we reach the climax, the world is at war.

Despite Jurowski understanding music on an intellectual level that I didn’t even know existed, let alone understand, he always manages to articulate what he wants by conjuring up an analogy that we ordinary folks can identify with.

My favourite note, which still exists in my score, came at the beginning of the Libera Me. Jurowski painted a picture for us, asking us to remember what it is like at church when worshippers fall into the rhythm of a prayer that everyone knows by heart. “Nobody is leading the beat”, he told us, “everyone just falls into a synchronised chorus. That’s how I want you to sing the opening recitative of the Libera me.” After our first attempt, he asked us to reduce the volume to “barely a whisper” and proclaimed his greatest simile of all, that we should “sing this passage as if from your own personal chapel”.

Watch Us

Verdi Requiem

Saturday 24 September 2016

7.30 pm, Royal Albert Hall

Brian Wright conductor

Katherine Broderick soprano

Susan Bickley mezzo-soprano

Peter Auty tenor

Graeme Broadbent bass

Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

London Philharmonic Choir

Huddersfield Choral Society

Royal Choral Society

Verdi Requiem