Alto Christine Allison is tepid on Mozart, but warm on his Requiem:

I know there are plenty more people out there who like Mozart’s music, as a whole, far more than I do. I’m the person who watches Amadeus and is rooting for the ‘villain’, Salieri, because Mozart is unbelievably annoying. Furthermore, as my musical training was in violin and not in singing, I’ve never performed any of Mozart’s choral works.

So here I am, writing about a composer I can sort of tolerate, and about a piece I’ve never performed in my life, to tell you why it’s amazing and why you all should come and listen to it. This is the definition of irony.

But before you give up on me just yet, let me clarify here that the Requiem is the glaring exception to my general feelings on Mozart. Given that my opinion of Mozart generally is tepid at best, it was a surprise to me the first time I heard the Requiem, that I really liked it.

It was even more of a shock that the more times I heard this piece, and as I rehearsed it with London Philharmonic Choir, I have come to love it.

Belief and Beyond Belief

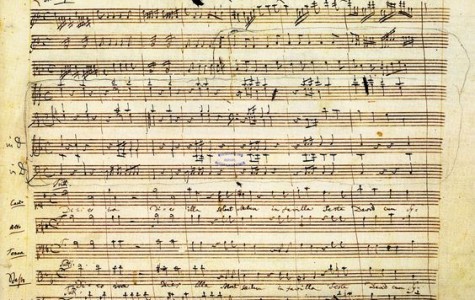

The Requiem is a unique work as Mozart didn’t write the whole thing, and others completed significant sections of it after him (the version that we are performing was completed by his pupil Sussmayr). But be that as it may, I don’t think that alternate authorship is the reason I love it so much. Rather, the fact that others have contributed to this work have given the Requiem a multi-faceted perspective on death, and that is what makes it stand out so much to me.

So, a nice, light topic for you all! But bear with me.

I don’t mean that I think about dying that often. But the concept of death is one of those ‘big questions’ that everyone has thought about at some point, and is especially apt given that the London Philharmonic Orchestra’s season theme this year is ‘Belief and Beyond Belief’.

The exploration of the concept of death, happens after death, and how those left behind respond to death – all of these ‘beliefs’ fit neatly into a Requiem mass.

There are prayers by the ‘dead’ or ‘dying’, pleading with God to not abandon them to punishment. There are prayers of the still-living, asking God to grant rest to those who have already passed. And, in the middle of it all, there are the prayers and texts which accompanied any kind of mass (the Ordinary), representing the life that goes on in the midst of death and mourning.

What I love about this piece is that the music presents, through the work of the different composers, multiple answers to the same ‘big questions’ about death. There is the perspective of someone who is extremely close to death (Mozart) as well as the perspective of the ones who have more time left on this earth (Sussmayr, or whoever’s complete version you hear). And the relative positions of both of these composers provide hugely contrasting views on the topic.

Rumbling Timpani, Crashing Brass and Frantic Violins

The bits that stood out were the rumbling timpani, crashing brass and frantic violins. Death is a final day of doom that Mozart knew was nearly upon him. The opening of the piece, the Introit, is itself a contradiction. Prayers for rest and eternal light are accompanied by sombre minor keys and the dirge-like accompaniment of the orchestra. There is then a barrage of text after text that clearly displays a fear of the day of wrath (‘Dies Irae’) and judgement (‘Confutatis’) that is to come. It seems to be the last, desperate pleadings of a man who knows that his time is up.

It is Mozart’s view of impending death that bookends the piece, but then, in the middle, the ‘Ordinary’ sections of the mass (texts that appeared in all masses) are almost the exact opposite. Although I had heard the piece before, the heartrendingly beautiful melodies (Benedictus) and glorious triumph (Sanctus) struck me as they had not before. What exactly could be so very beautiful and, well, happy, about death? Isn’t this the last work of a man who is terrified of the unknown that is upon him?

This performance gave me the opportunity to study the score further, which allowed me to see that many of the ‘happy’ bits were actually written by Sussmayr. It got me wondering, are these parts of the Requiem so much more hopeful simply because Sussmayr was still alive and didn’t feel the same anxiety as Mozart? It may well be.

Hope

Certainly there seems to be an element of hope in Sussmayr’s compositions that is significantly lacking in Mozart’s sections. But at the same time, there were equally beautiful sections, like the Recordare and Tuba Mirum, which had been written (for the most part) by Mozart. So not only were their huge contrasts between contrasts, but even the view of death by Mozart himself seemed to a mixture of emotions. Like any big question, the views we see in the Requiem are not black and white, but many shades in between.

In contrast to the memories of my youth, the parts that really appealed to me this time around were these sections, the ones that spoke of blessing and hope. A lot of has changed since I was younger – my views on ‘big questions’ are more complex and more nuanced, and so in more recent listenings and rehearsals of the Requiem, I don’t just notice the terror in the music, but the other messages as well, the other beliefs, including the beauty and the hope.

One might think that a piece composed by more than one person would be like two random puzzle pieces jammed together. Yet, with all the disparate perspectives, even with Mozart’s own ‘mixed message,’ the Requiem works. And to be honest, it more than just ‘works’ – the two seemingly contradictory views on death and dying are, in this piece, so closely meshed that they are two, complementary sides of the same coin.

Requiem masses tend to be heavily geared towards either the ‘doom or gloom’ (think Verdi) or comfort (think Brahms), but here in Mozart’s work, they are perfectly balanced. I listen to this piece and tremble at the ‘acrid flames’ of the Confutatis (which, by the way, has one of my favourite bass/tenor interplays of all time – listen out for it!). But I also rest in the tranquillity of the Benedictus, letting the flowing melody of the violins and soloists wash over me.

I love this piece because it can be so terrifying, yet heart achingly glorious; it is sobering and full of anxiety, but equally full of peace and reconciliation.

Exploration of the Big Questions

I think that I love the Requiem so much because it is a journey. It is a journey that comes full circle, with what is perhaps Mozart’s final prayer for himself, that as his death approaches, he will be granted eternal rest.

It’s an exploration of one of those ‘big questions’ that everyone thinks about at some point in their life. Everyone has different views, like Mozart and Sussmayr, and this piece is so appealing because it shows those different views in a manner in which they do not clash, but blend perfectly.

No matter where you stand on death, life, or life after death, the Requiem will speak to you. Even as our views and perspectives of such big questions change within our own lives (as they have from my childhood until now), the Requiem will stay with you and still is effective through that change.

It is belief, portrayed in its many contrasts, and yet fully compatible – a belief that is able to change with each listener, even FOR each listener – that makes this work so masterful.