If you think that title sounds rather dramatic and poetic you’d be absolutely right, for these three poems by Emily Dickinson and John Donne form the lyrics of John Adams’ extraordinary choral symphony Harmonium which showcases his rigour of “classic” minimalism with the lyrically tonal word-setting of them. Their drama and atmosphere pervade the music. We’re delighted to be joined in this performance by the BBC Symphony Chorus along with the London Philharmonic Orchestra and their Principal Conductor Edward Gardner on the 8th November at the Royal Festival Hall.

Composed in 1980, this towering choral symphony set in three movements is one of the earliest major works of American composer John Adams (b.1947) and was created for the opening of Davies Symphony Hall, the home of the San Francisco Symphony. Adams tells us that this symphony “was composed in 1980 in a small studio on the third floor of an old Victorian house in the Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco. Those of my friends who knew both the room and the piece of music were amused that a piece of such spaciousness should emerge from such cramped quarters. The title of the work was all that survived from my initial intention to set poems from Wallace Stevens’s collection of the same name.”

Composed in 1980, this towering choral symphony set in three movements is one of the earliest major works of American composer John Adams (b.1947) and was created for the opening of Davies Symphony Hall, the home of the San Francisco Symphony. Adams tells us that this symphony “was composed in 1980 in a small studio on the third floor of an old Victorian house in the Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco. Those of my friends who knew both the room and the piece of music were amused that a piece of such spaciousness should emerge from such cramped quarters. The title of the work was all that survived from my initial intention to set poems from Wallace Stevens’s collection of the same name.”

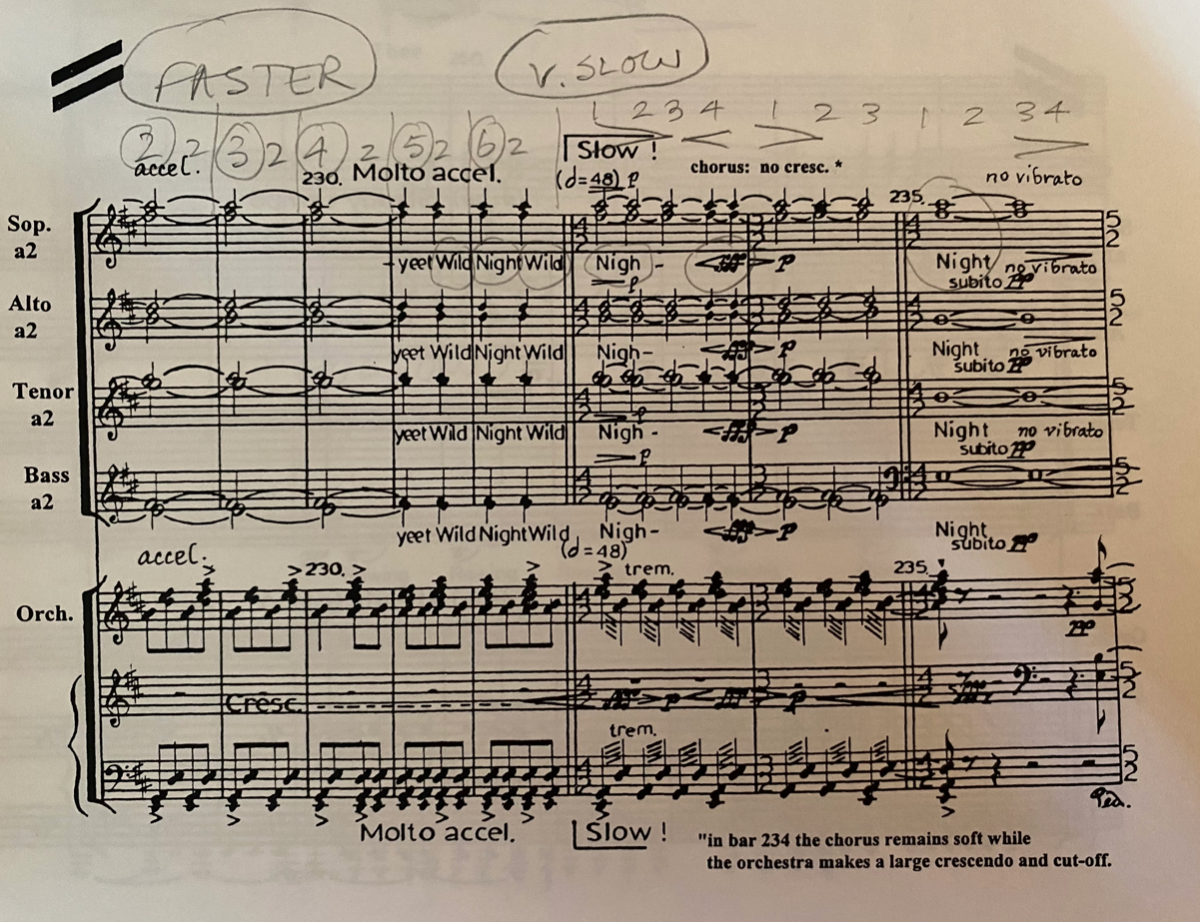

In the opening movement, Negative Love, Adams builds literally everything, even the text, from nothing, from repeated rhythmic ‘no’s to the vibrant, bright chords that “give fuel to their fire”. Essentially Harmonium is about good vibrations, that’s the nature of its music, and provides an intricate tapestry of sound, with bright vocal threads and driving brass and percussion rhythms. Walls of harmonious sound and repetitive rhythms build up throughout the piece. Undoubtedly the highlight of Harmonium is the transition into the final movement Wild Nights where a massive orchestral crescendo climaxes with an ecstatic harmonic shift into the entry of the choir.

Edward Gardner, says of this Symphony: “I love John Adams’ music. Harmonium is for me one of his great works, it’s such an exuberant, pure, joyous piece. Something I think Adams does so brilliantly is keeping the rhythm alive and there’s this idea of the energy bubbling within the texture of the music. The middle is serene and slow but the outer movements have this completely infectious heartbeat to them which I’m sure the audience will feel completely connected to. The music appears out of almost nothing and the final movement is so intoxicating – it will send any audience away with a smile on their face and an enhanced love of classical music.”

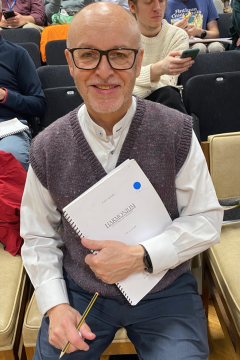

But whilst the outcome of Harmonium is brilliant and intoxicating, rehearsing this piece is not quite such a joyous experience as it’s quite challenging to learn. Geoff Walker, who sings bass in the LPC and is also an organist and chorus director himself, doesn’t feel quite the same as Ed about Harmonium – yet – but he is looking forward to the final result:

“To be honest, my preference is not really for this type of music so I thought carefully about signing up for the concert, but I did so in the end because although Harmonium is technically of the minimalist genre (which is not my favourite), there’s more to it than that and Adams uses a thicker orchestral texture which makes it much more interesting. When it comes to rehearsing, this kind of music is not intuitive; the rhythms are very complex and it gets pretty fast at times so you have to think about it quite a bit. Maybe because I have a mathematical background I tend to think of ways to approach it numerically as it were, in other words with lots of counting! I also think how I would approach it with my own choirs if I was teaching it to them: I would show them techniques to help manage some of the more difficult vocal and rhythmic challenges and I’m applying those things to myself so hopefully it will become more and more natural to sing by the time of the concert.

“To be honest, my preference is not really for this type of music so I thought carefully about signing up for the concert, but I did so in the end because although Harmonium is technically of the minimalist genre (which is not my favourite), there’s more to it than that and Adams uses a thicker orchestral texture which makes it much more interesting. When it comes to rehearsing, this kind of music is not intuitive; the rhythms are very complex and it gets pretty fast at times so you have to think about it quite a bit. Maybe because I have a mathematical background I tend to think of ways to approach it numerically as it were, in other words with lots of counting! I also think how I would approach it with my own choirs if I was teaching it to them: I would show them techniques to help manage some of the more difficult vocal and rhythmic challenges and I’m applying those things to myself so hopefully it will become more and more natural to sing by the time of the concert.

A friend of mind who was Musical Director of the Swingle Singers, and is now conducting local choral societies, is helping ordinary people to sing all kind of tricky and rhythmic pieces, such as the Swingles tend to sing. He might say don’t try and read the rhythm, just feel it and think of it as a certain kind of mindset, e.g. jazz or pop. We could definitely apply this approach to the Adams – for example when you have 3 rather than 2 beats in a bar so you have to count one, two over a three beat – maybe it’s not quite as complex as it first looks and you need to feel it more rather than just try to read the music.

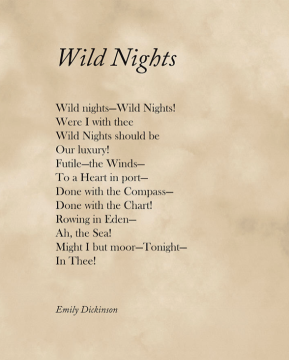

Our chorus director Madeline is a great communicator and she helps us a lot with singing techniques, the actual physicality of the piece and its rhythms. Also, her enthusiastic explanations of the poetry and the poets make a real difference and make you feel much more connected to the music. It’s so helpful to have good background information to the text and the music from the person directing it, especially when you learn for example that Wild Nights would have been an outrageous poem for a woman to have written in the mid 1800s – and then to have a contemporary composer put this in a modern sonic setting of how he might imagine Wild Nights now. I think that using the texts of two very famous poets is a really good choice by Adams. The poems are very powerful within themselves and it is pretty exciting at times, and also poignant. I wonder what Emily Dickinson would think if she heard her poems sung like this?”

Emily Dickinson, who wrote Wild Nights and Because I could not stop for Death, was a woman writing way ahead of her time. The passion in Wild Nights is something totally unimaginable for any of woman of the mid 1800s to be expressing openly, let alone one who lived in the deepest modesty and conservatism and rarely ever left her home. Born in Amherst, Massachusetts, Dickinson is said to have lived mainly in seclusion and in her later life never actually left her bedroom. A prolific writer, her relationships were all through correspondence and during her lifetime only one of her letters and ten of her 1800 poems were every published, and even they were edited. It wasn’t until after she died in 1886 that her work became public and she rose to become one of America’s greatest and most original poets – sitting alongside Walt Whitman, who wrote the poetry set by Vaughan Williams in our previous concert.

Emily Dickinson, who wrote Wild Nights and Because I could not stop for Death, was a woman writing way ahead of her time. The passion in Wild Nights is something totally unimaginable for any of woman of the mid 1800s to be expressing openly, let alone one who lived in the deepest modesty and conservatism and rarely ever left her home. Born in Amherst, Massachusetts, Dickinson is said to have lived mainly in seclusion and in her later life never actually left her bedroom. A prolific writer, her relationships were all through correspondence and during her lifetime only one of her letters and ten of her 1800 poems were every published, and even they were edited. It wasn’t until after she died in 1886 that her work became public and she rose to become one of America’s greatest and most original poets – sitting alongside Walt Whitman, who wrote the poetry set by Vaughan Williams in our previous concert.

John Donne, whose poem Negative Love opens the Symphony, was writing much earlier (around 1600) and was completely focussed on love in his text, but not the every day kind of love. This poem expresses a unique and paradoxical love that transcends physical and intellectual levels ascending in the manner of Plato’s Symposium. It argues that true love is not found in superficial qualities or rational understanding but in a mysterious and indefinable essence.

LPC chorus director Madeline Venner shares how she feels the music connects to the words of each of the three poems:

“The first movement, Negative Love by John Donne, is an extraordinary musical painting of love which is working its force at a level that is beyond the rational. The music conveys this by giving us ‘something’ that although we know is highly organised, somehow bypasses our ordinary rational musical facilities and really accentuates our sensuality and sensitivity, so we’re just sitting there experiencing this music and passion unfolding. The movement is tightly organised; it’s an extraordinary trick that Adams plays in the composing of it as we have wave upon wave of building sound and increasing speed in which it eventually climaxes with extraordinary force.

“The first movement, Negative Love by John Donne, is an extraordinary musical painting of love which is working its force at a level that is beyond the rational. The music conveys this by giving us ‘something’ that although we know is highly organised, somehow bypasses our ordinary rational musical facilities and really accentuates our sensuality and sensitivity, so we’re just sitting there experiencing this music and passion unfolding. The movement is tightly organised; it’s an extraordinary trick that Adams plays in the composing of it as we have wave upon wave of building sound and increasing speed in which it eventually climaxes with extraordinary force.

The second movement sets the Emily Dickinson poem Because I could not stop for Death, which is an unasked for encounter. In it she goes on a carriage ride with death and it’s a moment where her mind is opened, in fact all our minds are opened, to her (and our) mortality. The sonorities are much more muted and open and there is a kind of innocence in the way the journey is related. The music manages to combine an inexorable forward momentum as it ticks along but also somehow has time suspended; this is again one of those wonderful magic tricks of Adams’ composition.

The last movement, Wild Nights, is a fire really which begins with kindling and a few flickers and which then grows and grows until these huge orchestral flames are licking at us – and then there is an explosion of intense heat and light when the choir comes in, and this is just passion writ large. There is a kind of wild and crazy desperation to it really which takes us outside the normal demands of choral singing. The demands are so, so far beyond what we would expect and then there is this building and building to a sublime climax after which the music ebbs and subsides and leaves us with an oceanic feeling. The new rhythm of this section parallels Emily Dickinson talking about rowing on the sea. She is this lone voice – as in her extraordinarily lonely life – and this idea of her constantly rowing on the sea when she craves to moor, but can’t, shows that there she is again alone. The music of the final profound length of this last paragraph of the whole work maps the sense of the ebbing and subsiding of the water, and the motion of it from which there is no rest or escape.”

Soprano Helen Cheshire has only just joined the Choir and is really excited to be singing this piece as her first concert with us. She’s also our youngest member and has just come to London to study International Relations and Chinese at the London School of Economics:

“I’ve always enjoyed singing and I really took to choir in school, particularly chapel choir and the a capella choir. I love the communal aspect of singing in choirs and I really love it when everyone harmonises perfectly, it makes your heart sing. I knew as soon as I arrived in London that I had to find a choir to be part of. As I’m half Chinese, Confucius was always part of my life – he really liked the art of rituals and thought that they brought people together as a community and so I really love the way choirs are structured in to SATB and the way they interact as a community of voices, that’s now how I kind of understand what Confucius means about the art of rituals.

“I’ve always enjoyed singing and I really took to choir in school, particularly chapel choir and the a capella choir. I love the communal aspect of singing in choirs and I really love it when everyone harmonises perfectly, it makes your heart sing. I knew as soon as I arrived in London that I had to find a choir to be part of. As I’m half Chinese, Confucius was always part of my life – he really liked the art of rituals and thought that they brought people together as a community and so I really love the way choirs are structured in to SATB and the way they interact as a community of voices, that’s now how I kind of understand what Confucius means about the art of rituals.

One of the things I love about singing in a choir is the interesting and different challenges of learning the music, that’s what makes me want to sing and learn new pieces. I was thinking the other day when we were rehearsing about how everyone was so in tune, and it’s so lovely. It made me wonder how can you get so many people singing at the same pitch at the same time – it’s so cool, but of course, that’s the London Philharmonic Choir!

I don’t know the Adams piece at all but I love it so far – it does sound harmonious and I love the harmonies. I just love the way that the otherwise really simple individual parts interact to say something beautiful. If you look at the lines individually they look relatively easy but the timing and counting and staying together is tricky – and not losing where you are, that’s quite a challenge. I want to be better at counting to be honest as that’s vital in this piece. As I’m a newbie, everyone is so lovely and helpful but I don’t just want to rely on other people in the choir so I’m working hard to get this right by myself. I have a relatively bad sense of pulse but I’m good at remembering musical patterns and rhythms so I’m focussing on those. By the time of the concert I want to feel confident and know it as well as everyone else.

As you might imagine, I’m a bit nervous about this first concert as it is THE London Philharmonic Choir but I am also so excited about performing this piece. I love the sound of performing in big places in a big choir and one of the biggest things about being in the LPC is that we can sing in the Royal Festival Hall and the Royal Albert Hall. I’m also hoping my mum and sister will be at this first concert of mine – I will be so proud to sing to them as part of this choir.”

Come and hear us

Saturday 8th November 2025

7.30pm, Royal Festival Hall

Edward Gardner conductor

James Ehnes violin

London Philharmonic Orchestra

London Philharmonic Choir

BBC Symphony Chorus

Beethoven Violin Concerto

John Adams Harmonium