Marking the 400th anniversary of William Shakespeare’s death, Bass Richard Miller, currently completing a degree in composition and conducting at the Royal College of Music, looks at the the bard’s influence on choral repertoire.

Serenade to Music

I was recently fortunate enough to perform Vaughan Williams’ enchanting Serenade to Music with the Choir of St. Michael’s Church, Camden Town at a come-and-sing event. Very few of the singers had even heard of the piece before, and I was delighted to see how much they enjoyed working on it. Having been asked to write this article, there seemed no better work to focus on – it’s arguably the best known choral setting of Shakespeare and, in my opinion, the most successful pairing of a composer with his words.

Serenade to Music was originally composed for a concert celebrating the great conductor Sir Henry Wood’s golden jubilee (McGuire, 2013). The piece is a setting of text from Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice and is written for sixteen soloists with a standard sized orchestral accompaniment. At its premiere in 1938, it’s said that the composer Sergei Rachmaninoff (who was playing his own iconic 2nd Piano Concerto at this same concert) was moved to tears by the beauty of Vaughan Williams’ music (Miner, 2015).

“The Man that Hath no Muisc in Himself

So what is it about the music that makes it such a glorious pairing? Well, for a start, the piece is written in D Major, considered in the Baroque period to be “the key of glory” (Steblin, 1996), and though the piece often moves through different tonal centres, it rarely ventures into harmonic territory that is remote of this key.

In fact, the one point in the piece where it does venture outwards is at its darkest, most unsettling moment, in which Shakespeare’s text alludes to “the man that hath no music in himself”- surely no coincidence.

The influence of the early twentieth century French composers on Vaughan Williams is well documented, not least the influence of Maurice Ravel, with whom he studied for three months between 1907-08. After studies with Charles Wood at Trinity College, Cambridge and Hubert Parry and Sir Charles Villers Stanford at London’s Royal College of Music, as well as a brief period in Germany taking lessons with Max Bruch, Vaughan Williams came to the conclusion that he “was lumpy and stodgy … and that a little French polish would be of use” (Composer of the Week; Vaughan Williams – The French Connection, 2016).

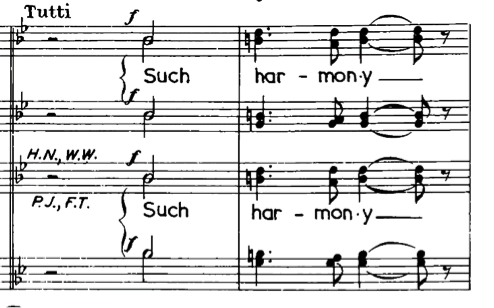

Not that this tuition with Ravel, who was three years younger than Ralph, wiped out the influence of the three great English composers; one aspect of Vaughan Williams’ music that certainly came from them was his aptitude for choral writing, and especially his considerable talent for word painting. Consider, for instance, the glorious moment in the Serenade to Music when he jumps from unison to homophony on the words ‘such harmony’, fulfilling the emphasis of the word ‘harmony’ with a jump from Bb Major to the much brighter G Major.

Proms Success

Sir Henry wrote to Vaughan Williams shortly after the first performance to thank him for the piece, and to tell him he believed the piece had “lent real distinction” to it (Vaughan Williams, 1964). It must have been a clear favourite of the conductor and his audiences alike; it was performed each year for the next four Proms seasons (1939-1942), and has received twenty-five performances at the Proms in total (BBC Proms Archive – Serenade to Music, n.d.) – number twenty-six is scheduled into this year’s Last Night.

More often than not, the piece is performed by a full chorus and was even arranged for solo violin and orchestra. In this latter arrangement, the choral writing is seldom redisbursed around the orchestra, and it needn’t be: the orchestral music that surrounds it is beautiful in its own right, and the material is more than strong enough to stand on its own two feet.

If I didn’t know the piece, I wouldn’t necessarily miss the voices. However, knowing the vocal versions so well, I always do miss the voices. Furthermore, I feel that the beauty of the piece is down to the partnership of the music and the text; the text, already very musical in its wondrous poetry, is perfectly complimented by the music. Vaughan Williams doesn’t intrude upon Shakespeare’s musings, and nor does he sentimentalise them in any way; the text and music coexist together magnificently with little effort.

Three Shakespeare Songs

The Serenade to Music is a serenely beautiful piece, but it’s just one of an abundance of choral music associated with Shakespeare. Also by Vaughan Williams, there are the beautiful Three Shakespeare Songs, consisting of partial settings of The Tempest and A Midsummer Night’s Dream (and incidentally, both Thomas Ades’ and Benjamin Britten’s respective operatic adaptations are well worth a listen).

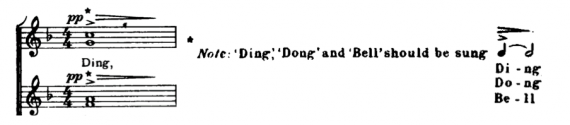

In the central movement of his Three Shakespeare Songs, The Cloud-Capp’d Towers, Vaughan Williams summons up a cathedral-like depth with wide-spaced chords that seem to allude to his Fantasia on a Theme of Thomas Tallis, and utilises his characteristically perfumy harmonies, with a tonality that never really settles. In the first movement, Full Fathom Five, he deploys the “ding-dong bell” fragment from the text chorally, rather successfully, ensuring that the effect of a bell’s decaying ring is achieved by closing the vowel sounds onto the ‘ng’ and ‘ll’ sounds (nasal and labiodental continuants, respectively).

Full Fathom Five

Full Fathom Five has proven to be a particularly attractive text for composers to set. Charles Wood, who taught Vaughan Williams at Cambridge University, set it as a standalone choral work, whilst Richard Rodney Bennett used it alongside Shakespeare’s The isle is full of noises and texts by Spenser and Marvell in his brooding choral suite Sea Change. In contrast to Vaughan Williams, Bennett actually scores the piece with bells, which appear in the other movements too (Bennett, 2005).

In Laurence Olivier’s film adaptation of Henry V, Sir William Walton’s score calls for a chorus that, until the end, is wordless, used as a separate group in the orchestral palette (Howes, 1965).

Michael Kennedy notes that a lot of the earlier scenes are a sort of pastiche of the music of Renaissance composer William Byrd and, in addition to Walton’s use of the tabor and harpsichord, the wordless chorus seems to give the music a very old feel, whilst his own distinctive harmonies keep it rooted in the 20th Century. For the end credits of the film, Walton employs the characteristically celebratory nature of his music as the chorus sings Deo gratias Anglia redde pro victoria! (Give thanks, England, to God for victory), the Agincourt carol.

Bob Chilcott’s arrangement of Touch Her Soft Lips and Part from Walton’s score for Henry V features in his compilation of ten Shakespeare settings. In anticipation of this significant anniversary year, Novello has released their Shakespeare Choral Collection, edited by David Wordsworth, containing 26 choral settings by 20th and 21st Century composers ranging from Charles Wood to Dame Judith Weir, current Master of the Queen’s Music.

400 years after Shakespeare’s death, it is clear that he continues and will continue to inspire the artists of our own time. Though few choral settings of Shakespeare are in the frequently heard repertoire, it’s clear that there is a wealth of music out there – and what better time to start delving in to it?

Richard Miller sings bass in the London Philharmonic Choir, and is currently completing a degree in composition and conducting at the Royal College of Music. He is Principal Conductor of the Royal College of Music Students’ Film Orchestra, Artistic Director of the St. Cecilia Ensemble and Director of Music at St. Michael’s Church, Camden Town.

Recommended recordings of Serenade to Music:

R. Vaughan Williams, Serenade to Music, Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra and Choir, Vernon Handley (EMI)

R. Vaughan Williams, Serenade to Music, Various Soloists, London Philharmonic Orchestra, Sir Adrian Boult (EMI)

Recommended further listening:

- Sir Richard Rodney Bennett, Sea Change

- Sir George Dyson, Agincourt

- Alexander Goehr, Take But Degree Away from Two Choruses

- Jonathan Dove, Our Revels Now Our Ended (also being performed in this year’s Last Night of the Proms)

- George Benjamin, Sometime Voices